It’s the last activity. The one everyone wants to do. Outgoing winterers (myself included) have absolute priority. But between weather watches (my job), bad weather and birders’ rest days… I couldn’t go before the penultimate day of operation.

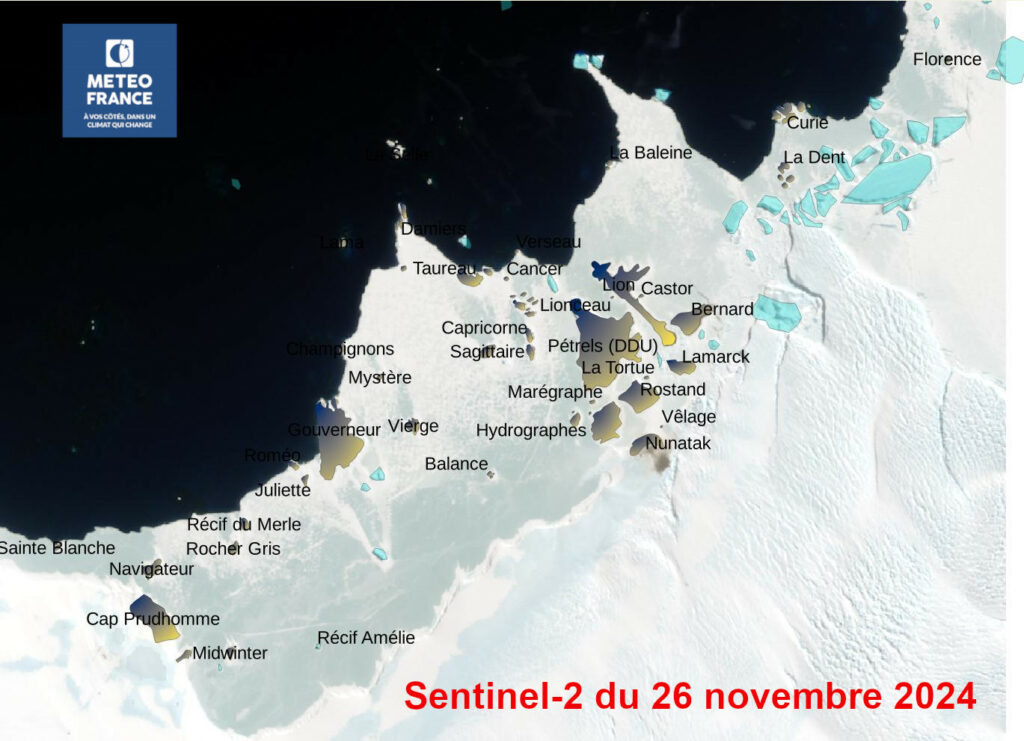

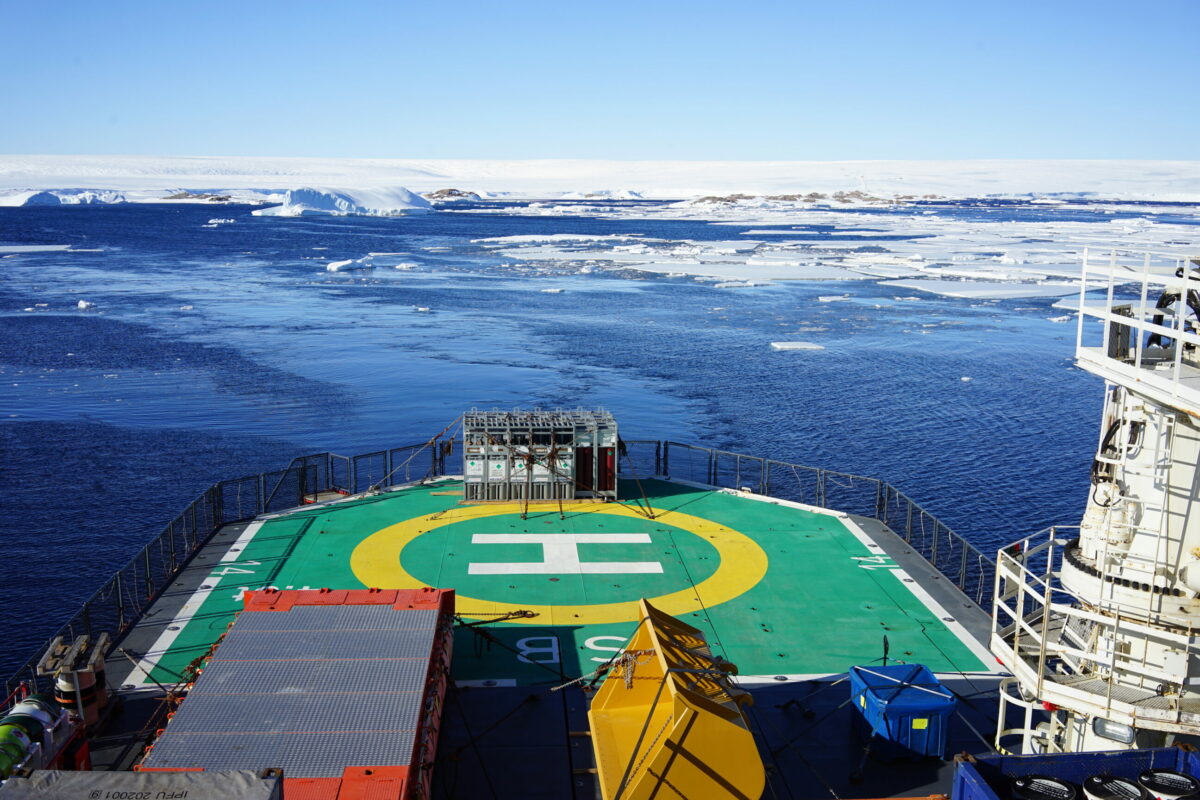

So I went on Nunatak on December 2, with a group of neophytes: Lise, Narcisse (new baker) and Alex (helicopter pilot) and experts: Doumé (transponder specialist), Léo (country birder), Natacha and Amandine (new winter birder) for the professionals. We set off with two pulkas of equipment (everything we needed for the parks was already on site). The weather was magnificent.

The Emperor penguin chicks are big now. I’ve watched them hatch, grow and be attacked by skuas and giant petrels. But it’s been a good two months since I’ve been to Nunatak. The colony has spread out a lot. The chicks measure 80cm and weigh some 15kg. They gather in nurseries and are looked after by the few remaining adults when the others have already gone out to sea to feed.

Four lightweight barriers are used to park the chicks without the adults. A wooden park is placed for catches. Two processing lines are set up.

An ornithologist enters the park and captures a chick. He places it on the shelf and grabs its beak. On the other side of the fence, we (the neophytes) put a sock over the chick’s head, covering its eyes but not its beak. The birder places the chick with its back to us. We pick it up by putting our arms under its fins and lift it up. When we’re lucky, it struggles until its legs are in the air. Otherwise, when we’re unlucky, it struggles all the time.

As the beaks and claws of penguins are free to injure us, we wear our orange jackets (which are very sturdy), work gloves (which are annoying to remove) and our mask to protect our eyes.

Penguin fins are used to propel them through the water when swimming and hunting. They are very thin, flat and strong. We hold the chicks under their wings to prevent them from dislocating their shoulders while struggling. The corollary is that they flap their fins as they struggle and hit our forearms. It’s like being hit by a wooden instrument. A pleasure …

Once you’ve got a penguin in your arms (and it’s quiet), it’s cute, soft and doesn’t smell like Adélie penguins. We take them to a team of ornithologists. Léo (or Doumé) takes the penguin by the torso, while we hold it by the feet. The chick flips onto its belly and Léo gets on top. He removes the down between the tail and one leg. He takes the transponder reading to check that the bird has not yet been transponded. He disinfects and uses a kind of gun to inject a chip under the animal’s skin (like seals). The penguin feels nothing at this point and doesn’t move at all. Meanwhile, Amandine (or Natacha) measures the bird’s beak with a caliper.

We take the chick back onto our laps. Amandine measures its wings, while Léo plucks a few feathers from its torso and feels the penguin’s belly to see if its stomach is full. Léo then holds the right wing while Amandine disinfects and takes a blood sample. Léo puts the chick in a hood and carries it to a gallows where the animal is weighed. The bird is painted on the belly and wingtips with green paint. Then it’s set free. Meanwhile, Amandine has disinfected all the utensils and prepared the transponder.

One of us (neophytes) writes in a notebook the time, measurements (beak, wings, weight), transponder numbers, blood and/or feather samples, moult stage and whether the chick has food in its stomach. Another rests, making sure that the chicks in the park don’t run away.

We made two pens. One contained sweet little chicks. The other contained teenagers who were ready to go to sea and wanted to do battle. We took care of 33 chicks in one afternoon. I can see why birders get tired. I’ve got bruises on my arms myself. As always with Biomar Tourism, DDU’s travel agency run by the ornithologists in the Biomar building at Dumont d’Urville, we went as far away from the base as we could (1 km) and had cake and hot chocolate for 4 o’clock.